December 2014 by Brian A. DiGangi, DVM, MS, DAVBP (Canine/Feline)

Audience: Veterinary Team

Are animal shelters and rescue groups getting it wrong with feline heartworm disease?

A Balancing Act

Adoption of pets from animals shelters is on the rise.1 For most cat shelters, preparing our pets for a healthy life includes vaccination against common infectious diseases and testing for feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). In fact, even though scientific studies have shown that only around 2% of healthy cats are infected with FeLV or FIV,2 many animal re-homing organizations require such testing prior to adoption or transfer.

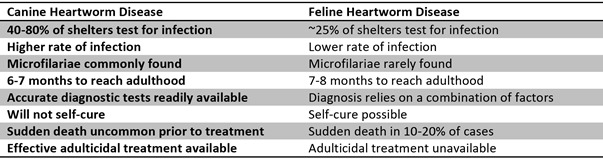

Meanwhile, as many as 10% of shelter cats in some regions of the country are infected with heartworms, with less than one quarter of shelters in high-risk areas prioritizing testing for feline heartworm disease.3, 4 Compare that to between 40 and 80% of shelters that test dogs for heartworm disease.5

Are we neglecting our responsibility to our feline friends?

Not Just Small Dogs

We all know that cats are unique. Different from our canine companions in many ways, their physiologic response to heartworm infection is one more thing to add to the list. They’re not just small dogs – and our disease management protocols must be altered to take their unique responses into account. Understanding the disease prevalence, life cycle, clinical signs, and prognosis will guide us in the development of rational management protocols for shelter pets.

Prevalence and Risk Factors

It is true that cats can get infected with the same heartworm that infects dogs (Dirofilaria immitis), however, they are more resistant to this infection. The true rate of feline heartworm infection is hard to pinpoint due to difficulties in diagnosis; however, most studies suggest that cats are infected at somewhere between 5 and 15% of the rate of dog infections in the same geographic area.6

One reason for this lower rate is the fact that cats are simply less attractive meals for the mosquitoes that transmit the parasite from host to host.7 There is no known age or sex predilection for infection and "indoor-only" cats are just as likely to become infected as are those that have outdoor access.8

The bottom line is that wherever dogs are at risk for heartworm disease (i.e., everywhere in North America), so are cats!

Life Cycle

The life cycle of the feline heartworm follows a similar progression as in the canine host. A heartworm infected host (usually, but not necessarily, a dog) is bitten by a mosquito vector that ingests the L1 stage (also known as microfilariae) of the parasite.

After approximately two weeks within the mosquito under the right conditions, the L1 molts through L2 and into the L3, or infective phase. The L3 are injected into a new host (a dog, cat or ferret) through a bite from the mosquito.

The larvae migrate through the soft tissues of the animal as they move toward the heart and lungs. During this migration, L3 larvae develop into L4, immature adults, and finally mature adults. In the cat, this migration process takes 7 - 8 months to complete (versus 6 - 7 months in the dog). The lifespan of mature adult heartworms in the cat is 1 - 2 years.6

While the heartworm parasite follows the same general path to adulthood in a feline host, it is a much harder and less successful journey than in the dog. Due to the cat’s robust immune response to heartworm infection, some data suggest that greater than 90% of infective L3 larvae do not make it all the way to adulthood.

Consequently, only one or two adult heartworms are typically found in a fully mature feline heartworm infection. That may not seem like a big deal compared to the scores of adult heartworms often found in canine hearts, but the comparatively smaller size of the feline heart and lungs make those one or two heartworms just as dangerous.

One additional but important difference in the course of feline heartworm infection as compared to that in dogs is the relative lack of microfilariae. Microfilariae are found in less than 20% of feline infections; when they are present they are transient, low in number and survive only a few weeks.3, 8

In addition to fewer opportunities for production (remember, only 1 - 2 adult worms are present, often of the same sex), the feline immune system is also very effective at removing any of the microfilariae that are circulating in the bloodstream. Fortunately, this means that cats are unlikely to be a significant reservoir for infection of other animals.

Clinical Signs

The unique characteristics of heartworms in the feline host help explain the differences in disease progression that cats undergo after infection.

There are two points in the disease process that cause the majority of clinical signs that affect our cats: (1) the arrival (and death) of the juvenile worms in the blood vessels of the heart and lungs, and (2) the death of adult heartworms.6

The most common clinical signs of the arrival and death of juvenile worms – such as a high respiratory rate, difficulty breathing and coughing – are often referred to as "heartworm-associated respiratory disease," or HARD. These signs are also shared by other feline respiratory diseases such as asthma and allergic bronchitis.

Less common signs of heartworm infection include vomiting, neurologic signs, collapse and sudden death.9 Many cats are able to overcome this phase of the disease process – and in some cases completely clear the heartworm infection – but not without damaging the small blood vessels in the lungs during the process.6, 7

When healthy adult worms are present, they work to suppress the cat’s immune response to their presence – often resulting in no clinical evidence of disease. In one scientific study, 28% of cats diagnosed with heartworm disease had no clinical signs of infection.9

However, the death of adult heartworms is usually more problematic. The degenerating parasite can cause an intense inflammatory response and can block the blood supply to the lungs (pulmonary thromboembolism). In these cases, the cat may experience a sudden and occasionally fatal respiratory crisis – even if only one worm is present.6, 7

Prognosis

Although a fully mature heartworm infection can be lethal to a cat, there is some good news.

The feline immune system takes full advantage of each opportunity to fight disease caused by heartworms as they progresses through their life cycle. This generally results in about 80% of cats clearing their infection within 2 to 4 years after diagnosis.

However, approximately half of those who do not survive long-term will die suddenly from acute respiratory failure.9, 10, 11 Those cats who do experience clinical signs of disease have a harder road to travel. In one study, one-third of cats diagnosed with heartworm disease died or were euthanized due to severity of their disease on the day of diagnosis. The median survival time of heartworm infected cats who did survive past the day of diagnosis was 4 years.9

Box 1 highlights some of the differences between canine and feline heartworm disease:

Managing Feline Heartworm Disease in the Shelter

Prevention

As with most other medical and behavioral challenges we manage in animal populations, prevention of feline heartworm disease is easier, cheaper and more humane than awaiting the development of disease and trying to create a treatment plan in a resource-scarce environment.

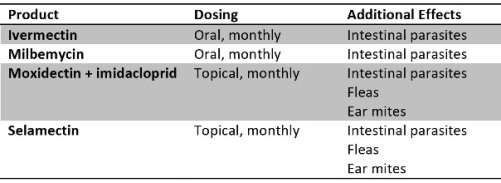

As with dogs, prevention of feline heartworm disease can be achieved with monthly administration of one of a variety of commercially-available products (Box 2, below). Such products have the benefit of preventing and treating additional parasitic infections – many of which are already part of standard intake protocols in most shelters:

Off-label use of ivermectin products is also commonly reported by shelters as a cost-saving means of ensuring cats remain protected.4 All these products can be administered safely regardless of current infection status.6

Despite the availability, ease of use and effectiveness of feline heartworm preventives, one survey found that nearly 70% of shelters in areas of high prevalence of infection did not administer such medications to their feline guests. Added expense and the misperception that cats need to be tested prior to administration of preventives were the primary reasons for avoiding the practice.4

As will become evident when we explore the complicated issues of diagnosing and treating heartworm disease in cats, administering monthly preventives is the most effective and achievable step that any sheltering organization should strive for when it comes to managing this disease.

Should administration of preventives to the entire feline population be unachievable, practical risk assessment can be employed to determine those to prioritize for treatment. For example, one shelter may elect to treat only those cats that were picked up as strays, those selected for adoption directly from the shelter, or those with clinical signs of disease that could be attributed to heartworm infection. It is important to note that none of these "risk factors" are proven to indicate greater risk of infection, so the end goal should remain universal treatment for all cats in the population.

Diagnosis

Establishing a definitive diagnosis of heartworm infection in a cat can be quite a challenge. It relies on a combination of clinical and diagnostic findings rather than a single screening test result as is often the case in dogs.

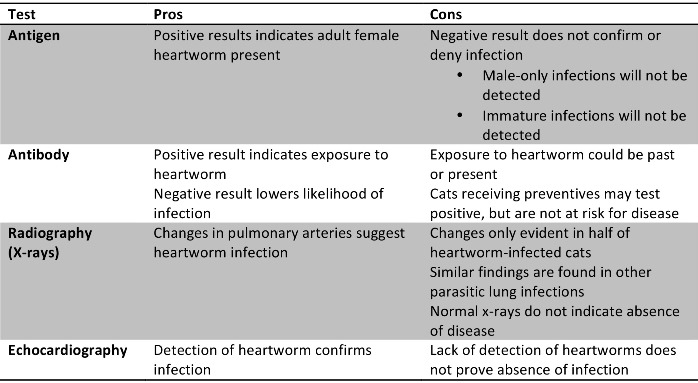

Blood tests for heartworm disease in cats are limited to antigen (testing for the parasite itself) and antibody (testing for the body’s response to an infection) tests. Although testing for microfilariae as is commonly recommended in dogs is also possible, it is highly prone to error as cats seldom have circulating microfilariae for the reasons discussed previously.

Feline heartworm antigen testing is commercially available, easy to conduct, and provides instant results. However, it is not a very sensitive means of heartworm detection in the cat (i.e., there is a high chance of false negative test results).

Since the test detects mature female heartworms, false negative results can occur in immature infections and in male-only infections, two conditions that are common in feline heartworm disease. Therefore, while positive results would prove infection, negative results do not mean a cat is clear from infection.6

Antibody testing can be conducted by sending a blood sample to a diagnostic laboratory for diagnosis, a procedure that carries additional cost and generally requires a few days before results are obtained. Alternatively, point-of-care antibody test kits are also commercially available.

Accuracy of antibody test results vary widely based on the stage of larval development at the time of sampling.12 For this reason, although a negative antibody test means an infection is less likely, it does not mean a cat is clear from infection.6, 9 Positive antibody test results are even more troublesome to interpret, as a positive antibody test merely indicates that a cat has been exposed to heartworm disease. A positive result does not mean that a cat is currently suffering from an infection. It has also been reported that as many as 30% of cats receiving heartworm preventives may have positive antibody test results due to exposure to the parasite; since they are on preventive, such cats are not at risk for disease progression.13

Additional diagnostic clues can be found through the use of x-rays and echocardiography. About 50% of cats with heartworm disease will have evidence of enlarged pulmonary arteries on x-rays of their lungs.14 However, these findings can be found with other parasitic infections such as roundworms (Toxocara) and lungworms (Aelurostrongylus).

In the hands of an experienced ultrasonographer, the heartworms themselves can often be seen during an echocardiogram. As with the other testing modalities, the absence of any of these x-ray or echocardiographic signs does not mean that a cat is clear from infection.6

Box 3 summarizes the pros and cons of each testing option:

For all of these reasons, screening all cats for heartworm infection is generally not a good use of resources in any environment, but particularly so in shelters. The most accurate method of diagnosing feline heartworm infection is through a combination of veterinary examination findings and diagnostic tests.

For this reason, pursuit of a diagnosis is probably best limited to those cats who are exhibiting clinical signs that may be attributed to heartworm disease and/or for whom knowledge of their infection status will result in a significant change in their disposition pathway. In such cases, each finding and test result can be used to "build a case" that indicates the likelihood of infection.

In the case of antigen and antibody testing, one scientific study evaluated the accuracy of combining these two tests to make a diagnosis. Researchers found a lower chance of erroneously declaring a cat positive (i.e., higher test specificity) if only one test was used, but there was a lower chance of erroneously declaring a cat negative (i.e., higher sensitivity) when the two test results were combined.12

Practitioners can use this information to develop testing protocols that make the most sense for their organization or for an individual patient. For example, if a positive test result places an individual cat at risk for euthanasia, then ensuring accuracy of positive test results is of the utmost importance. On the other hand, given the severity of disease that can develop in some cats, an erroneous negative test result may mean a cat does not receive the appropriate treatment and monitoring that is necessary to protect its health and welfare.

Treatment and Monitoring

There is no known safe and effective adulticidal treatment available for feline heartworm disease. There is no scientific evidence that any treatment intended to kill adult heartworms in dogs will safely do so in cats and increase their infection survival rate.6 Administration of melarsomine, the compound labeled for treatment of adult heartworms in dogs, is not as effective in cats and its administration is frequently fatal.7, 8 For these reasons, "treatment" of feline heartworm disease focuses on controlling clinical signs related to the disease process.

Corticosteroids (such as prednisolone) and bronchodilators are the mainstays of medical management of feline heartworm disease.

Daily administration of corticosteroids at a tapering dose over a six-week period is often an effective means of reducing inflammation associated with the disease and minimizing signs of respiratory discomfort. Clinical signs (and perhaps x-ray findings) should be re-evaluated after this course of treatment; additional courses of corticosteroids may be prescribed if necessary.6, 8

There is no evidence that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin, are of any benefit. In fact, they may actually worsen lung damage.6 Although not without significant risk or expense, surgical removal of feline heartworms has been successfully performed in severe cases.8

The symbiotic relationship between Dirofilaria immitis and Wolbachia bacteria is well-known. Consequently, much attention has been devoted to the use of antibacterial therapy targeting Wolbachia organisms in the management of heartworm disease.

Elimination of Wolbachia can inhibit heartworm larval development, sterilize female heartworms, kill adult heartworms, and reduce inflammation in the host.7 Tetracycline antibiotics, such as doxycycline, are usually administered for this purpose.

Although there is no evidence to demonstrate their effectiveness in the management of feline heartworm disease,6 there is also no reason to suspect that they would be any less effective than in dogs. In fact, the reduction of inflammation in the lungs – a key benefit of eliminating Wolbachia organisms and the major cause of fatalities in feline heartworm disease – may allow for more effective feline treatment protocols and lower the risk of sudden death.7

Continued monitoring is an important component of the treatment plan for feline heartworm disease. The information obtained from repeating diagnostic tests such as antigen and antibody measurement, x-rays, and echocardiograms can be helpful in determining whether or not medical management is effective as well as determining an individual cat’s risk of further complications.

Most scientific experts recommend repeating some diagnostic tests at 6 - 12 month intervals.6, 13 The exact frequency will depend on the needs of the individual cat; the exact tests used will likely be similar to those used for initial diagnosis (to allow for comparison of results throughout the disease course).

Particularly in the shelter setting, careful consideration should be given to how the information from repeat testing will be utilized. The pros and cons of interpreting the various testing methodologies have been discussed above, but the most useful parameters in disease monitoring are likely to be antigen testing and lung x-rays if these tests were utilized in disease diagnosis.13

For example, being able to demonstrate that a previously "antigen positive" cat is now "antigen negative" may assist in adoption. Similarly, demonstrating normal findings on x-rays of the lungs when they were previously abnormal may indicate reduced risk of serious complications, and may ease concerns of a transfer partner.

Perhaps the most useful and most important measure of progress can be obtained by looking at the animal itself. Veterinary examination and monitoring the presence and absence of clinical signs are keys to ensuring good welfare regardless of the disease process. The ability of cats to hide signs of illness makes hands-on examination and careful observation of even greater importance.

Conclusions

Feline heartworm disease is a complicated issue! It is no surprise that few shelters devote the resources to diagnosing and managing this disease. To do so would probably not be the best use of resources in most cases.

And that’s the good news – managing feline heartworm disease doesn’t require piles of money or fancy equipment. With a little veterinary guidance, it can be accomplished with careful observation and attention to cat comfort – things that are already top priority in every cat shelter!

Resources

There are a variety of easily accessible resources to help veterinarians and shelters learn more about feline heartworm disease. These resources may also be useful when communicating with adopters and transfer partners when relaying information about individual cats.

The American Heartworm Society offers scientific guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and management of feline heartworm disease, along with basic facts, incidence maps and infographics to help explain the disease to pet owners.

The Companion Animal Parasite Council showcases important facts, disease maps and expert articles on all kinds of companion animal parasites, including feline heartworms.

References:

1. American Humane Association & PetSmart Charities. 2012. Keeping pets (dogs and cats) in homes: A three phase retention study. Phase I. Available online at: http://www.americanhumane.org/aha-petsmart-retention-study-phase-1.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2014.

2. Levy JK, Crawford C, Hartmann K, et al. 2008 American Association of Feline Practitioners’ feline retrovirus management guidelines. (2008) 10; 300-316.#

3. Companion Animal Parasite Council. Current advice on parasite control: Heartworm – feline heartworm. (2014) Available online at: http://www.capcvet.org/capc-recommendations/feline-heartworm/. Accessed November 30, 2014.

4. Dunn KF, Levy JK, Colby KN, et al. 2011. Diagnostic, treatment, and prevention protocols for feline heartworm infection in animal sheltering agencies. Vet Parasit, 176: 342-349.

5. Colby KN, Levy JK, Dunn KF, et al. 2011. Diagnostic, treatment, and prevention protocols for canine heartworm infection in animal sheltering agencies. Vet Parasit, 176: 333-341.

6. American Heartworm Society. Current feline guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of heartworm infection in cats. (2014) Available online at: https://heartwormsociety.org/images/pdf/2014-AHS-Feline-Guidelines.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2014.

7. Kramer LH. The Role of Wolbachia in Heartworm Infection. In: Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine, Ed. JR August. Saunders Elsevier: St. Louis. 2010. p. 19-26.

8. Litster AL, Atwell RB. 2008. Feline heartworm disease: a clinical review. J Fel med Surg, 10: 137-144.

9. Atkins CE, DeFrancesco TC, Coats JR, et al. 2000. Heartworm infection in cats: 50 cases (1985-1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc, 217:355-358.

10. Genchi C, Venco L, Ferrari N, et al. 2008. Feline heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection: a statistical elaboration of the duration of the infection and life expectancy in asymptomatic cats. Vet Parasit, 158: 177-182.

11. Venco L, Genchi C, Genchi M, et al. 2008. Clinical evolution and radiographic findings of feline heartworm infection in asymptomatic cats. Vet Parasit, 158: 232-237.

12. Snyder PS, Levy JK, Salute ME, et al. 2000. Performance of serologic tests used to detect heartworm infection in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 216: 693-700.

13. Baral RM. Lower Respiratory Tract Diseases. In: The Cat, Clinical Medicine and Management, Ed. SE Little. Elsevier Saunders: St. Louis. 2012. p. 861-891.

14. Schafer M, Berr CR. 1995. Cardiac and pulmonary artery mensuration in feline heartworm disease. Vet Radiol Ultrasoun, 36: 499-505.

Brian A. DiGangi, DVM, DABVP

Dr. Brian DiGangi received a Bachelor of Science degree in Animal Science with a minor in Nutrition from North Carolina State University in 2001, and graduated from the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine (UF CVM) in 2006. While at UF CVM, Dr. DiGangi completed clinical externships in both shelter medicine and exotic animal medicine, and co-founded the University of Florida Student Chapter of the Association of Shelter Veterinarians. He volunteered at the county animal shelter on a regular basis, organized spay-neuter wet labs for veterinary students, regularly participated in a large feral cat trap-neuter-return program and fostered animals for local rescue organizations.